As Flutter developers, we create new widget classes every day. Often, we don’t think twice about those widget APIs. We throw a few properties in a constructor and move on. It’s easy to create widget APIs that make sense in the moment, but don’t play well over time. Let’s talk about an easy mindset that you can use to design better widget APIs that work well in the long run.

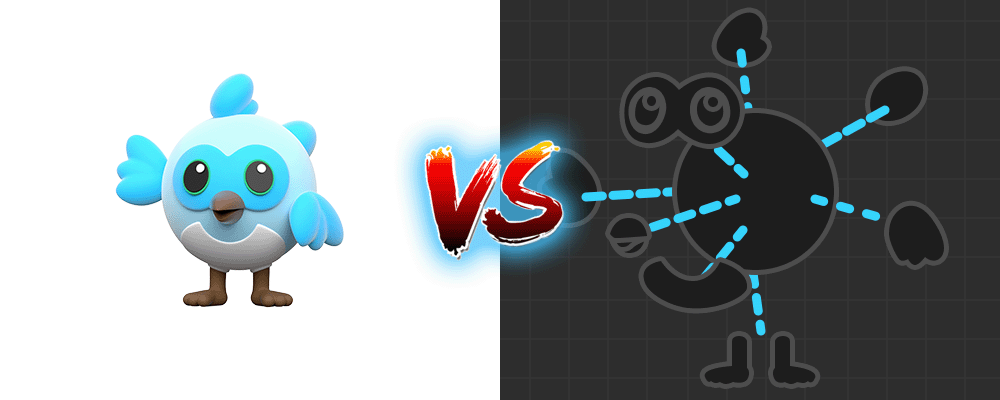

Are you an app developer or a toolkit developer?

When you sit down at your desk to build a new widget, ask yourself if you’re an app developer or a toolkit developer. This isn’t a question about your job title or your role. I mean right now, for this widget, are you operating as an app developer or a toolkit developer?

An app developer designs and builds widgets for the purpose of implementing a UI specification. These are the widgets that users see and touch. These are called user-facing widgets.

A toolkit developer designs and builds widgets for other developers. These are called toolkit widgets.

Any app of sufficient size will include both user-facing widgets and toolkit widgets. The first step to design a great widget is to decide which type you’re building.

How to design user-facing widgets

By definition, user-facing widgets are the end of the line. They’re the final piece of code that renders the experience that you ship to users. These widgets only need to honor the details in your UI design specification. You don’t win any points for adding more complexity beyond what’s required.

Your first goal when designing a user-facing widget is to meet the expectations of your UI specification.

ProtectListItem(

status: ProtectStatus.ok,

label: \"Hallway\",

onTap: () {...},

);

A user-facing widget might have a few configurable properties, such as the label on a button, or a button’s tap callback. If you’ve accumulated more than a handful of properties in a user-facing widget, you’re probably doing it wrong.

Once a user-facing widget meets the configuration needs of the UI spec, the next priority is speed of development. This means that other developers can quickly read and understand your widget code. Give your widget a meaningful name. Do the same for each widget property. Add appropriate Dart Docs for the class and each property.

Careful naming, and effective documentation, might seem like a task for toolkit developers. And it is. But it’s also a critical task for app developers. Your code is written once, but it may be read thousands of times. Moreover, while it’s tempting to declare your code “self-documenting”, in practice, it’s usually impossible to write self-documenting code. There are details within your lines of code, and then there are details between your lines of code. Find the details in between the lines, and explain those details in concise Dart Doc comments for each class, method, and property.

Once your code fulfills your spec, is as simple as possible, and contains useful names and comments, stop!

Apps need to move fast. You need to ship new features, ship experiments, and fix bugs. Don’t add a bunch of properties for the sake of it. Push your changes and move on.

The reason that you don’t need to worry about the future when you’re building user-facing widgets is because you own the app code, and no one else depends upon it. When the UI specification changes, and you need to adjust the behavior of a widget, you don’t have to worry about breaking other projects, or other teams, or other features. It’s cheap to alter user-facing widgets. So spend your bandwidth on throughput, not infinite configuration.

To summarize, when designing user-facing widgets, first, solve for your UI specification, second, solve for speed of development, third, move on.

How to design toolkit widgets

Widget design gets more interesting when you’re designing a toolkit widget. Toolkit code is expensive to change. By definition, other developers depend upon your toolkit widgets. Based on what you’re building, it’s possible that projects within other companies depend upon your toolkit widgets. The more developers that depend on a widget, and the greater the distance between you and those developers, the more careful you need to be with the design process.

Toolkit developers need to minimize code churn, so that other developers aren’t forced to routinely change their code to stay in compliance with the toolkit widget’s API. Additionally, toolkit developers need to support the broadest set of use-cases possible so that they don’t disenfranchise developers.

The tools at our disposal are widget composition and property configuration. Both of these tools give developers control over the final behaviors of a toolkit widget. The difference between these two tools is the direction that they point in the widget tree.

Widget composition

Widget composition allows developers to express different use-cases around a toolkit widget, by altering the widgets that sit higher up in the widget tree. We call those widgets “parents” or “ancestors”.

Consider a document editor, like Super Editor. A document editor could be represented by one single widget, which includes all user behavior for the editor. But now imagine that you need to create a document editor that uses the same document layout, but you need different gestures for interacting with the document. You want your editor to do different things based on taps, double-taps, triple-taps, and drags. What do you do?

If the entire document editor is one big widget, without any smaller widgets, then changing gesture control requires that you build an entirely new document editor, and re-invent everything. It’s a horrendous situation. And yet, toolkit developers put app developers in situations like this all the time.

On the other hand, if the document editor is comprised of one widget for document layout, and another widget for gesture handling, then you, the app developer, can re-use the document layout widget, and wrap it with your own version of a gesture handler. This reduces the amount of re-work by 99%.

What’s the technical difference between these two situations? The difference is that the first solution provided a monolith that came with an “all or nothing” offer. The second solution still provided a widget for a full document editing experience, but that document editor widget was composed of other public widgets, which effectively solved smaller, common document editing problems. Namely, document layout, and document gesture interaction.

Developers often try to stuff every possible configuration into widget properties. Widget properties have their purpose. We’ll discuss them next. But not every type of control should be a property on a widget. Attempting to provide a property for every possible configuration is guaranteed to deliver two results. First, your widget constructor will be absurdly large and complicated. Second, you’ll still fail to account for all sorts of use-cases. It’s a losing proposition. Effective toolkit developers know when to rely on composition up the tree, instead of property configuration down the tree. Your job, as a toolkit developer, isn’t to solve all problems for all developers. Your job is to solve one problem for all developers. Let your users make their own decisions about everything else.

Of the two available tools, widget composition and configurable properties, widget composition is far more powerful, and grossly under-utilized by the community. If you’re unsure about how to facilitate ancestor/descendant relationships, the easiest way to setup these relationships is by passing GlobalKeys. When an ancestor holds a GlobalKey that’s attached to a descendant, the ancestor can directly talk to the descendant. This, for example, is one of the ways to separate a document editor’s gesture handler widget from the document editor’s layout widget. Toolkit developers should be completely comfortable with using GlobalKeys to split independent widget responsibilities.

Configurable properties

Configurable properties allow developers to express different use-cases inside of a toolkit widget, by altering the widgets that sit lower in the widget tree. We call those widgets “children” or “descendants”. Configurable properties can also alter the behavior of a RenderObject that belongs to a widget.

Widget properties are unavoidable when designing widgets, so every Flutter developer is surely familiar and comfortable with using them. The important thing to recognize about widget properties is that they should only configure details that can’t be configured by widget composition.

Consider the Image widget. The Image widget has a property called fit. The fit property determines how the image is sized, based on the available space. The image can be sized to take up all available space, even if it cuts off part of the image. Or, the image can be sized so that you can see the entire image, even if it leaves some space empty. Or, the image can be distorted to fit the exact width and height of the available space, even if it changes the aspect ratio of the image.

The Image widget is solely responsible for painting image pixels to the screen. No other widget can take over that responsibility. The Image widget literally exists for this purpose. Therefore, it wouldn’t make any sense to try to control an Image's fit from an ancestor widget. The way the image pixels are scaled to fit the available space is fundamentally a responsibility of the Image widget, and so it’s controlled by a property on the Image widget.

Widget properties can also include child widgets. For example, a Padding widget takes a single child. A Column, Row, and Stack each accept an arbitrary list of children. A Scaffold accepts an appBar, body, drawer, and floatingActionButton. Each of these properties configures the structure of the widget tree beneath the widget in question. They configure the descendants.

As a rule of thumb, when a toolkit widget needs to configure its descendants, or a toolkit widget needs to configure a behavior which can only be implemented by the toolkit widget, then you should use widget properties to achieve that configuration. Everything else should be left to widget composition, because doing so leaves as many doors open as possible.

You should try to predict the future

When designing user-facing widgets, I told you to never try to predict the future. It saves you nothing, but always costs you something. That calculus is reversed when you’re working on toolkit widgets. Toolkit widgets deserve, and require, thorough analysis of likely future requirements. Throw YAGNI in the trash.

As previously mentioned, changes to toolkit widgets are costly. Every API change breaks your users. If you break your users a few too many times, they’ll stop using your toolkit widgets. The only way to minimize breaking changes is to predict the future. On the one hand, humans are terrible at predicting the future. On the other hand, the only thing worse is to make no attempt at all.

The most powerful tool I’ve found when it comes to predicting the future is to find and respect the natural axes of change. To understand axes of change, you must first understand the difference between essential complexity and accidental complexity. Essential complexity is the complexity that’s baked into the problem, itself. Nothing you do can ever reduce the essential complexity. It doesn’t matter what language or framework you choose. It doesn’t matter what design patterns you implement. It doesn’t matter what algorithms you invent. The problem, itself, has complexity, and it’s called essential complexity. Accidental complexity is everything else. All overhead added by decisions you make, qualifies as accidental complexity. The term is a little misleading. Accidental complexity doesn’t mean that you accidentally added complexity - most accidental complexity is on purpose. All solutions add some amount of complexity on top of the problem, because the tools you’re using to solve the problem force some amount of complexity upon you. Therefore, every toolkit widget that you build will contain the essential complexity of the problem, as well as the accidental complexity of your tools and choices. Now, back to the axes of change.

Axes of change are places within the problem, itself, where requirements are likely to change independently. The easiest way to understand axes of change is to look at an example.

InteractiveViewer is a Flutter framework widget that makes it easy to build a scene that the user can pan and zoom.

InteractiveViewer.builder(

transformationController: _controller,

minScale: 0.1,

maxScale: 1.6,

builder: () {...},

);

Assume that you're using InteractiveViewer in your app. You want everything that InteractiveViewer does, except you don't want InteractiveViewer to respond to Apple Pencil interaction. You want the Apple Pencil to draw shapes instead of panning the viewport up and down and left and right. What do you do? It turns out that you can't do anything. You have to throw away all of InteractiveViewer and start over, because InteractiveViewer combined layout behavior with gesture behavior.

Imagine that Flutter got rid of InteractiveViewer and replaced it with various compositional widgets, like the following:

InfiniteCanvasGestures(

controller: _orientationController,

child: InfiniteSceneBuilder(

orientation: _orientationController,

builder: () {...},

),

);

This new version is slightly more complicated than the first one, but the widgets are now broken down by the natural axes of change. There's one widget that responds to gestures, called InfiniteCanvasGestures, and another widget that handles layout for the scene, called InfiniteSceneBuilder.

With the second widget structure, you would still need to replace InfiniteCanvasGestures with your own version that includes Apple Pencil support, but you could still use InfiniteSceneBuilder as-is. Also, the layout behavior is much more complex than the gesture behavior, so it's a big win to re-use the InfiniteSceneBuilder widget.

Fundamentally, InteractiveViewer is solving two independent problems. The first problem is the layout and caching of infinite 2D content. The second problem is the application of user gestures to the (x,y) offset and zoom level of the content. By respecting these axes of change, and solving these problems with independent widgets, these toolkit widgets give greater power and flexibility to app developers.

Some developers, who are overly technical, think that axes of change are something that they invent by way of clever API design. That’s not correct. The order is backwards. Axes of change existed before you ever investigated the problem, let alone solved it. The best you can hope to do as a developer is to discover the API which best respects the axes of change. You’re not inventing some tech toy from scratch. Instead, you’re trying to fit your API around the existing problem as tightly as you can, like sucking a piece of plastic around the shape of a mould. The problem, itself, has moving parts. Your toolkit widgets should strive to have the same moving parts.

The most common mistake developers make

There’s a great irony in most widget development. It’s the irony of app developers trying to create toolkit widgets, and toolkit developers accidentally creating user-facing widgets. The reason for this mistake is personal insecurity.

App developers churn out features. They’re the assembly line workers of the software development industry. A bunch of sophisticated parts appear before them, and the app developer’s job is to quickly assemble those parts into the final product. The problem is that those app developers spent as much time in college as the toolkit developers who created the sophisticated parts. The app developers feel like they’re wasting their talents on the assembly line.

To make themselves feel like “real software engineers”, app developers start adding a bunch of properties to widgets. They start inventing their own requirements for the future so that they feel like they’re engineering something. And these additional properties aren’t just some boolean flags and strings. No. App developers like to go all in by adding a bunch of streams to their widgets. Everybody knows that you need a Computer Science degree to figure out how to work with streams, so we should have streams everywhere! At the root of this problem is an insecurity about one’s place in the development ecosystem. By filling app teams with Computer Science grads, there’s an incentive for those developers to prove their intelligence and knowledge. They do so by grossly overcomplicating the assembly of parts provided by others. What those developers should do, is either recognize that they’re working on an assembly line and focus on throughput, or find a toolkit team to join. But overcomplicating user-facing widgets isn’t helping anyone.

On the toolkit side, we find a personal insecurity that points the other direction. What’s the most embarrassing thing that can happen to a toolkit developer? The most embarrassing outcome is that nobody uses the toolkit widgets that the developer built. A toolkit developer wants to feel wanted, and needed. This insecurity leads to a false assertion. Toolkit developers think to themselves that the best way to gain adoption is to build the simplest tool possible. With the simplest possible tool, developers will be willing to try the tool, and they’ll love it, and the toolkit will have great success. But this assumption is usually wrong.

The job of a toolkit is to solve sophisticated problems by creating tools that can be used by all developers within a particular audience. If you’re a toolkit developer on an app team, your audience is all the other app developers on that team. If you’re a toolkit developer in the Flutter community, your audience is everyone in the world suffering from the given problem. Not only do the toolkit solutions need to match the variability of the audience, but they also need to be structured in a way that keeps them relatively stable over time. On the one hand, of course toolkit developers should strive for “ease of use”, but it’s critical that toolkit developers understand that “ease of use” is not the same thing as “simplicity”. Sometimes problems really are complex. When toolkit developers create simple tools, they massively over constrain the solution. Only a portion of the audience is able to use the tool. Over time, even that portion of the audience is forced out by their own evolving requirements. As a result, the toolkit developer’s focus on simplicity for the sake of adoption becomes the primary reason that the toolkit withers and dies. Toolkit developers should instead focus on the intrinsic complexity of the problem, identify axes of change, and then utilize widget composition and property configuration to provide a holistic solution to the entire problem. This is how a toolkit thrives, in the long run.

Conclusion

When you begin work on a new widget, start by asking yourself whether you're building a user-facing widget or a toolkit widget. If you're building a user-facing widget, optimize for visual polish and speed of development. If you're building a toolkit widget, optimize for composition and configuration. This simple decision process may not answer every widget design question, but it will consistently promote the most appropriate considerations and tradeoffs as you expand your widget portfolio each day.

If your team would like direct help with widget API analysis, consider consulting with Matt Carroll at SuperDeclarative!.

If your team would like to offload toolkit development to the Flutter Bounty Hunters, please send us a message.